If you are studying English literature or poetry, you will probably have come across many of Shakespeare’s sonnets.

And if you are asking, what is a sonnet, by the time you have read this article you will know how to identify them as well as comment on their thematic, rhymed and metrical aspects. In fact, you will probably be able to attempt writing your own sonnet poem.

What is a Sonnet?

If you are yet to set foot into the world of English literature, then keep reading. There are different types of sonnets but generally, the sonnet poem shares certain thematic similarities as well as aspects like structure, style, themes, and length. These conventions are what separate a sonnet poem from the many other forms of poetry available.

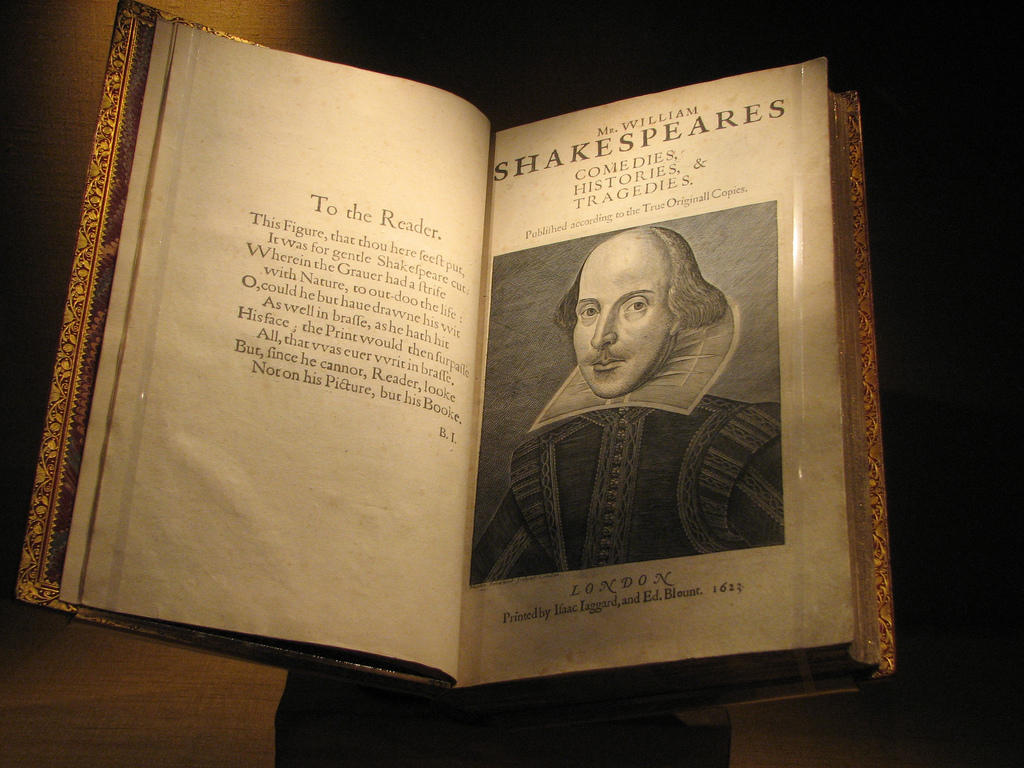

History of the Sonnet Poem

In the study of literature, one of the ways that poetry is categorised is by historical context. So to really understand what the poet is trying to achieve, you would need to understand the history of its poetic form.

To answer the question, what is a sonnet as simply as possible we would need to remember that sonnets (derived from the word “sonneto” meaning “little song”) are an Italian invention. Sonnets of the 13th century even though they were not yet formalised, inspired many great poets during the Italian Renaissance. Names like Dante, Petrach, and Cavalcanti did much to contribute to what we define as the sonnet poem today.

Over time, different types of sonnets emerged through the work of poets in England and France. Over the following centuries, poets from all over Europe began to add to the definition of what is a sonnet. In English speaking society, Shakespeare’s sonnets became some of the most famous literary works of the 19th century Romance period.

In addition to Shakespeare’s sonnets, poets like Keats, Wordsworth, and Shelley made huge contributions to this genre.

While poets are still writing modern sonnets today, there is some latitude for different types of sonnet, instead of the once-strict structure of yesteryear.

Reasons Why Sonnets Appeal to Poets

Whether it's Shakespeare’s sonnets or other types of sonnets, the appeal of this genre for today’s poets is mainly its association with big names in literature and the fact that it offers so much scope for study.

Another reason for its popularity is the brevity of the sonnet which is well suited to communicating emotion that is potentially lost in longer forms.

Finally, while the romantic themes of love associated with the sonnet poem allow for great flexibility, you will find that the many types of sonnet written today cover topics from politics to ice cream.

The Most Important Features of a Sonnet

Recognising the different types of sonnet poetry means that you will need to be able to recognise certain features.

Lines and Structure

Typically, much like Shakespeare’s sonnets, this poetry form has 14 lines but can be arranged in different ways.

For instance, in a Petrarchan sonnet, lines are grouped into two, octaves (eight lines) or sestets (six lines).

In Shakespeare’s sonnets, you will find three quatrains of four lines and a couplet of two lines.

The Volta

While voltas are present in many different forms of poetry, they are important to the sonnet. Meaning ‘turn’ in Italian, the volta indicates a moment of change in a poem. This could be theme, argument or tone. They usually occur after line eight in a poem and are recognisable with the use of words like ‘but,’ ‘however’ or ‘and’.

Iambic Pentameter

This may seem like an intimidating piece of jargon, but when broken down, it makes sense.

'Meter' refers to rhythmic structure (syllables and their arrangement), while ‘Penta’ is derived from the Greek word ‘five’. Therefore, the pentameter of a sonnet poem has something to do with five.

The word 'iamb' refers to two syllables, one is unstressed and the other is stressed. In an iambic pentameter, there are five in each line.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets use this form. Here is an example of stressed syllables from his Sonnet 18.

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

There are 10 syllables in the line, five of which are stressed. If we switch the stressed and unstressed syllables around, the lines become clumsy.

Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?

The Sonnet Series

Another answer to the question, what is a sonnet, is that they typically appear in a series. For instance, Shakespeare’s sonnets are numbered all the way to 154.

The Main Types of Sonnet

There are three main types of sonnet. Shakespearean sonnets, the Petrarchan sonnet and the Spenserian sonnet.

Each of these types bears the characteristics mentioned above: 14 lines, iambic pentameter, volta and sequence. Their main difference is their rhyming scheme.

Let’s take a closer look at all three main types of sonnet.

Petrarchan Sonnet

The Petrarchan sonnet is named after the Italian poet Petrarch (1304-1374) and is the earliest form of the strict sonnet poem.

It is divided into two stanzas broken up into an octave of eight lines, followed by an answering sestet of six lines. Here is an example of a typical Petrarchan sonnet.

London, 1802 by William Wordsworth

(A) Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour:

(B) England hath need of thee: she is a fen

(B) Of stagnant waters: altar, sword, and pen,

(A) Fireside, the heroic wealth of hall and bower,

(A) Have forfeited their ancient English dower

(B) Of inward happiness. We are selfish men;

(B) Oh! raise us up, return to us again;

(A) And give us manners, virtue, freedom, power.

(C) Thy soul was like a Star, and dwelt apart:

(D) Thou hadst a voice whose sound was like the sea:

(D) Pure as the naked heavens, majestic, free,

(E) So didst thou travel on life's common way,

(C) In cheerful godliness; and yet thy heart

(E) The lowliest duties on herself did lay.

Note the markings of the iambic pentameter in the first line and the volta in the eighth line.

The letters before each line represent a rhyming scheme, which in this case is ABBAABBA, CDDECE.

The Petrarchan sonnet poem usually begins with that ABBAABBA octave. Do note that the rhyme scheme of the sestet is most commonly CDECDE or CDCDCD.

The Shakespearean Sonnet

The English or Shakespearean sonnet follows a different set of rules which means when you ask what is a sonnet, you should specify the type too!

Shakespeare’s sonnet of three quatrains and a couplet has the following rhyming scheme: ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG and this is the main difference between the Petrarchan and Shakespearean sonnet.

Sonnet 130, by William Shakespeare

(A) My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun;

(B) Coral is far more red, than her lips red:

(A) If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

(B) If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

(C) I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

(D) But no such roses see I in her cheeks;

(C) And in some perfumes is there more delight

(D) Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

(E) I love to hear her speak, yet well I know

(F) That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

(E) I grant I never saw a goddess go,

(F) My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:

(G) And yet by heaven, I think my love as rare,

(G) As any she belied with false compare.

Note the use of the volta, however in the Shakespearean sonnet this can appear after the octave or as in the above example, at the start of the couplet. Here, it is being used to indicate a conclusion, summary, or counterargument to the previous three stanzas.

The first 12 lines describe the speaker’s mistress, comparing her most unfavourably to nature. However, the final couplet sees a complete change in tone despite the apparent flaws of the subject!

Sonnet 130 is a satire of other poets who tend to compare their loves to nature’s beauty.

The Spenserian Sonnet

A contemporary of Shakespeare, Edmund Spenser lived from 1552 to 1559. His sequence, Amoretti, was his main engagement with the sonnet form - and his other works included The Faerie Queene, an allegory about Elizabeth I, and The Shepherd's Calendar, a poem about shepherds, surprise surprise.

The Spenserian sonnet has a similar structure to a Shakespearean one, with three quatrains followed by a couplet. The interesting thing about the Spenserian sonnet is, of course, the rhyme scheme. Let's take a look at Spenser's Sonnet 75.

(A) One day I wrote her name upon the strand,

(B) But came the waves and washed it away:

(A) Again I write it with a second hand,

(B) But came the tide, and made my pains his prey.

(B) Vain man, said she, that doest in vain assay,

(C) A mortal thing so to immortalize,

(B) For I myself shall like to this decay,

(C) And eek my name be wiped out likewise.

(C) Not so, (quod I) let baser things devise

(D) To die in dust, but you shall live by fame:

(C) My verse, your virtues rare shall eternize,

(D) And in the heavens write your glorious name.

(E) Where whenas death shall all the world subdue,

(E) Our love shall live, and later life renew.

What would you say is happening here?

Compared to Shakespeare’s sonnets which follow ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG, Spenserian sonnets are different with their ABAB, BCBC, CDCD, EE rhythm.

You’ll find the volta in line nine where Spenser uses ‘not so’ to introduce a contradiction.

Playing with the Form

So as you can see, the sonnet poem has a distinct basic structure, however, it’s important to remember that many poets will take licence with both form and content.

Writing Your Own Sonnet

If you’re going to write your own sonnet you can select any style you like. But given that it lends itself well to the English language, this guide will use Shakespeare’s sonnet as a guide.

When it comes to writing a Shakespearean sonnet there are several rules to bear in mind. Most importantly, the style follows a specific rhythm, rhyme scheme, and format.

Follow this process to guide you:

- Select a subject to write about (Shakespearean sonnets are often about love).

- Write your lines using iambic pentameter (duh-DUH-duh-DUH-duh-DUH-duh-DUH-duh-DUH.

- Structure your sonnet using three quatrains followed by a couplet.

- Compose an argument so to speak that builds up from metaphor to metaphor, offers a counter-argument (the volta) in the concluding couple.

- Make sure that your sonnet is 14 lines in length.

A Step by Step Guide

1. Find Inspiration

While Shakespeare’s sonnets usually revolve around love, you could, choose any topic for a sonnet. You could even use a pop song for inspiration!

Check out Taylor Swift’s Shake It Off is a fun example of iambic pentameter in a modern context.

Other examples of lyrics sung in iambic pentameter are:

- One Direction – History

- Alessia Cara – Here (each foot’s extra stress on the downbeat make it a good example)

- Halsey – New Americana

- G-Easy or Bebe Rexha: Me, Myself and I

Note that these songs are not sonnets, however, they will give you an excellent feel for how to use iambic pentameter.

To see more popular songs in sonnet form ... make sure you check out how the lyrics of Beyonce and the BackStreet Boys have been turned into sonnets.

2. Master the Iambic Pentameter

To internalise the iambic ‘beat’, simply practice it while walking: left foot unstressed and right foot stressed, clap your hands or drum your fingers with a soft-LOUD, soft-LOUD

Mastering the iambic pentameter will help you achieve the correct rhythm as you write your sonnet.

Once you have chosen a topic to write about, internalise the iambic beat and you will find that writing your sonnet is a breeze.

Remember to introduce the situation in your first quatrain, follow an ABAB pattern to make sure that the third line rhymes with the first and the second rhymes with the fourth.

Here is an example of an ABAB quatrain:

Ago, I saw you walking fair one day

Though fear forbade my presence should come near.

Froze, the words that I could never say

Though in my heart remain so very dear.

Also, analyse it to see if it meets all the criteria for proper iambic pentameter quatrain:

- Each line comprises five iambic feet (in other words, 5 duh-DUMs).

- Line three and line one rhyme, while line two rhymes with line four.

- It sketches a situation (we ask why the speaker is afraid of approaching a situation and wonder what he or she wanted to say)

3. Play with Words

You’ll note a number of words in this stanza that would not usually be used in daily conversation.

This is one of the wonderful aspects of poetic licence which gives you permission to convey meaning through more creative expression and allows you to bend common language rules to expand word meanings.

Our great writer Shakespeare was famous for taking licence with word meanings and his frequent use of the word 'anon' is a good example.

The word anon, which dates back to 12th century English means immediately, straight away or forthwith. Through Shakespeare’s constant misrepresentation of the word, it now means in a while or a bit later.

We can tell why he loved that word: it is short and convenient and fits neatly into rhyme and iambic pentameter.

Using poetic licence is a great tool as long as you do not completely vandalise the language.

For instance, poetic licence will permit you to use the incorrect tense, like the word froze instead of frozen. This could demonstrate a greater sense of urgency in only a few letters, e.g. He was froze in fear.

4. Depict a Scene using 14 Lines

Depicting a scene using so few words will require that you use all the visual imagery and loaded words that you possibly can.

For instance, the phrase ‘fear forbade my presence to come near’ conveys much much more than ‘I had an awful anxiety attack and could not approach you, even though they convey exactly the same meaning, right?

This stanza enables the reader to view fear as a crushing and looming entity, even to the point of denying the speaker to approach someone. It’s so much more powerful than simply writing ‘anxiety attack.’

5. The Quatrain

The opening quatrain of our example provided an excellent start. So with the right rhyming, feet and visual pattern to outline our situation, it is now time for quatrain two.

Delight in how the sun kisses your cheek;

Tortu’r in how I wish that it were me!

Mere audience with you is what I seek

As though your heart were once again trusting.

What are the components that make this a valid quatrain?

In this stanza, we are told that the speaker is aware that he or she has broken the subject’s heart. Not the last line which was spat out with such self-loathing.

And we know that it is a sunny day.

This line cleverly builds up information that leads us into the next quatrain and, finally the couplet concludes the situation:

Ago, I saw you walking fair one day

though fear forbade my presence should come near.

Froze, the words that I could never say

though in my heart remain so very dear.

Delight in how the sun kisses your cheek;

Tortu’r in how I wish that it were me!

Mere audience with you is what I seek

As though your heart were once again trusting.

Ne’er! Your cry strikes such a cruel blow!

Ne’er! Your mien doth passion-tly aver!

How did I force love’s door on me to close

When soul and mind, it all I gave to her?

And then, Divine, the hand that turns your face!

Our eyes, searing, questing, entwine, embrace.

Note the growing passion all the way through; the third quatrain crescendos into fury and agony until the concluding two lines which are a direct contradiction to the rest of the poem.

Note the escalating use of poetic licence. In fact, you will see that the more passionate and desperate the situation becomes, the more license is used to express it all!

Final Tips for Sonnet Writing

The ability to internalise the iambic pentameter and employ poetic license is actually fairly easy compared to the kind of vocabulary you will need to master the classic sonnet. However, if you love words, you could draw on what you know and use a thesaurus to discover the most poetic and unusual synonyms to create your masterpiece.

Not only will a thesaurus provide just the word you are looking for, but it will also help you to find antonyms to creatively express the opposite of what you are feeling. Using antonyms is also a great way to produce literary irony!

As you can tell, a thesaurus is so much more than a dictionary, it also offers meanings to popular phrases and urban language.

Try Other Poetry Forms Too

The great advantage to being a poetry lover is that there are styles to suit every type of writer. Different types of poems can be used to capture the very heart of a variety of different types of situations.

Once you have tried the sonnet; you try short poetry forms like the humorous limerick or sophisticated haiku. An epic poem can impart a wide range of emotions, while a ballad poem is perfect for a lyrical arrangement. If you’re more into instant feedback and performance, then slam poetry in front of a live audience is for you. And if all of that doesn’t tweak your interest, why not try free verse poetry where anything goes?

Summarise with AI: